Misinterpreting traits of ADHD, Autism and other neurodevelopmental differences gets an early start in life. And of course it does: when we’re growing up, adults always have the upper hand in defining things for us.

We have a limited ability to communicate complex experiences we’re going through for the first time. Meanwhile, for various reasons, adults often choose to whip out a label rather than engage with genuine curiosity to explore whether that label has anything to do with the actual experience.

Learning that an apple is called an orange or that a whale is a type of fish is more easily rectified later with new information. The same is rarely the case for complex internal experiences like emotions or states of mind.

No wonder so many people go their entire lives without learning, for example:

- that the common labels of ‘stress’ and ‘anxiety’ describe something fundamentally different from their ADHD trait of perpetual mental restlessness,

- that their Autistic trait of sensory overwhelm might be behind experiences not explained by panic attacks, or

- that ‘having a hobby’ or ‘being obsessed’ are not accurate descriptions for the general neurodivergent trait of hyperfocus.

In our series of things we wish we knew about our neurodivergence as late-diagnosed neurodivergent adults, I invite you to explore the process I’ve identified for how others’ repeated mislabeling of our early neurodivergent experiences teaches us to self-censor our experiences, building up over time into full-blown internalised ableism.

Understanding this is important not just because of the massive hit it causes to our overall self-esteem, but also because this constant self-censorship is exactly what makes it so hard to discover the neurodivergent roots under a lifetime of false labels.

Your journey might not be the same as mine.

To paraphrase Joseph Campbell, each of us enters the dark forest at a different point and walks our own path. Regardless, we here at Weirdly have often found that points of realisation can overlap, inspire, or even be exactly the same.

And why peek into the dark forest? Well, the reward waiting for you at the end of this specific journey is the skill to finally get those itchy labels off and identify your own truths underneath.

So that’s your exercise as you continue below: see where the path looks similar. And who knows, following a trail that looks familiar might lead you to a realisation of your own.

‘This is what it feels like to go mad’

The noise filled my senses drip by drip as if Jackson Pollock himself started slowly pouring paint onto an empty canvas.

The moment I entered the grand entrance hall, it hit me. The smell of recently dried white paint the maintenance team had used to paint over the high ceiling, the doors, the many creaking window frames. Children were running around, parents were chatting to each other and the camp counsellors, all underscored by the constant, muffled noise of street traffic.

It was summer and the day was bright. The grand, white room felt increasingly hot. And soon, its whiteness burned, setting fire to my eyeballs, my lungs, my brain. I thought I must be going mad.

I was 10 and I knew with a savage certainty: this is what it feels like to go mad.

All I saw was the fine dust gathering on the leaves of a giant monstera plant in a corner, and the whiteness burst into colour, the maestro adding the final touch to his newest masterpiece: Jackson Pollock, Sensory Overload of a 10 Year-Old, 199X. Oil on canvas. The canvas: my brain.

This was supposed to be the introductory Meet & Greet event of the summer camp I was meant to go to. But after about five minutes I fled the grand room, ran up to my parents, and with a strained modulation in my ten-year-old voice I implored them to get me out of there.

Nothing had ever been more imperative than to get out of there.

‘But can’t you just stay?’ No, not one second longer. Get me out, please get me out. We have to go, we really have to go, now.

‘Oh, she’s just a bit stressed out,’ my father told the camp director by way of an apology for my obvious rudeness.

‘She’ll play a solo at the school orchestra’s concert tomorrow.’ My mother quickly put on a strained, apologetic smile.

The takeaway for me, other than feeling jittery and wrung out for the best part of a day afterwards: this violent dispersal of my sanity is called ‘being a bit stressed out’.

Right, there must be nothing wrong then.

How Internalised Rules Are Born

The sensations of that day etched themselves deep into my body and mind. So naturally, I remembered the verdict very well and repeated it to myself whenever I found myself in similar situations. ‘I’m just a bit stressed out, that’s all.’

Growing up we all operate on the internalised voices of others. Parents, teachers, and peers all like to evaluate or judge our behaviour and tell us what we are, how we perform, and how we feel. And we tend to accept these judgments — in the spur of the moment, it’s the quickest explanation to what otherwise may feel odd or worrying.

‘You’re just a bit kooky,’ they said when, at age 6, I kept watching the French dub of the Japanese documentary series La planète miracle over and over again until I memorised the entire 12-hour narration.

‘Others like to play, too,’ they said when I spent hours on the playground swing by way of trying to calm myself down. ‘But maybe you’re a bit old for that now.’

‘It’s normal if you can’t fall asleep now and then,’ they said when I first developed sleep disturbances at the age of 8.

‘These headaches run in the family.’

‘You’re just overly sensitive.’

‘It’s just a phase, you’ll grow out of it.’

‘You should just try harder if you want to change.’

‘If others can do this, then you can, too.’

Countless times I just accepted such statements without ever questioning them. I allowed them to overwrite, even outright erase the nagging feeling that something wasn’t right.

And, given enough time, they became The Truth (™), as I couldn’t remember their source anymore, only the reassuring feeling of simple explanations.

‘I am okay after all.’

Except, I never was.

The name of the game is internalised ableism

Had I known what I know now, I could have started to dismantle these false truths about the world and myself in it way earlier.

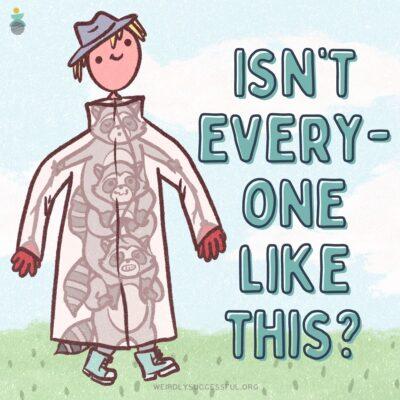

Had I known what I know now, I could’ve given myself the chance to entertain the thought that not everyone is a bit awkward, kooky, insomniac, anxious, and overly sensitive but otherwise ‘normal’ and capable — that some of my experiences cannot be normalised or trivialised.

But – I didn’t know. Decades of these false truths cemented the foundations of a misunderstanding of how I think of myself. A dysfunctional construct whose building blocks I could only start replacing once I learned the name of the architectural style it was built in: internalised ableism.

The effect of internalised ableism

But what does internalised ableism mean? Not on a theoretical level, but in actual practice. Here are some of the ‘rules’ I’ve observed:

- If, by mainstream societal standards, you look capable, if you get by (even if just barely), if you seem to be okay, that means you cannot be in need of support.

- Should you realise that you do actually need support, and communicate that you need support, it’ll get explained away as a minor shortcoming and never taken seriously enough. After all, ‘you look capable enough to get by’.

This is that pivotal point when figures of authority brush you off with phrases like ‘you should try harder’, ‘these are just excuses’, ‘get your act together’, or ‘all it takes is discipline’.

Figures of authority can appear in the form of parents, teachers, uncles and aunties, medical professionals, managers, HR, coaches, therapists, and politicians.

And don’t forget self-proclaimed representatives of societal norms: classmates, coworkers, customer service, acquaintances, random people on the street and on social media feeds…

Hear the phrases enough times, from enough sources, and they will become integral parts of your standard, your internalised truth that reinforces that you are indeed capable and that you do get by, regardless of how you’re actually feeling.

Soon enough, you start to overwrite your own truth and replace it with the voices you’ve heard around you.

This only sets you up for misunderstanding and misinterpreting yourself, your body’s signals and your mental health struggles. As a result, even when you can no longer tolerate to suffer in silence and reach out to someone for help, the key to the problem will be missing.

Dismantling our internalised ableism is the key to understanding

No wonder we only, finally, become able to entertain new truths once we start putting in serious effort to understand where the insomnia, the anxiety, the depression, and the sensory sensitivity really come from.

And this is when rational explanations and common, superficial therapeutic interventions peter out without leaving us in a significantly better place.

And on that note, let’s be mindful of the weight of this subject and take a breather here.

Paving the way to understanding – and healing

Stay tuned for part two, where I’ll go into the practical takeaways that came from learning about internalised ableism, including:

- the three big unlearning experiences around stress, empathy, and other people ‘having it all figured out’

- the a-ha moment of ‘not growing out of this’

- the Autistic self-reflection method I’ve developed for myself that helps me keep exploring and understand myself better

If you’d like to get notified when that’s out, get your free library card that comes with our newsletter subscription — and I specifically recommend the Adaptation Explorer Workbook which is a great resource if you’re building a neurodivergence-friendly life for yourself.

Download the Adaptation Explorer Workbook

Grab our workbook to discover your own neurodivergent adaptations – 15 unique pages of worksheets for collecting adaptations for work, study, rest and sleep, and to care and advocate for yourself.

Download now from The Library, our free resource hub.

ADHD & Autism on the Rise: Are There More Neurodivergent People Now?

ADHD & Autism on the Rise: Are There More Neurodivergent People Now?

Leave a Reply