“How did no one ever notice??”

The amount of times this sentence is heard in our house, along with the dramatically exaggerated waving of arms, would definitely qualify for a sitcom catchphrase.

You see, reader, I’m what they call “late-diagnosed”.

“Late” is relative, of course. For ADHD, “late diagnosis” can mean anything from above 60 for those above 60 to 25 for those who are 25. For Autism, some guidelines even go down to 12 as “late”.

My own ADHD stamp (with the bonus traits from a handful of other neurodivergent conditions) came at 37, with the fancy PDF attachment. We already knew, we just didn’t know know.

Once confirmed, though, not one week goes by when I don’t do, say or remember something that so clearly reveals a neurodivergent trait that’s always been there.

So how did no one ever notice?

As this question became our hyperfocus, rabbit hole and, eventually, this website, it finally made sense.

All the descriptions were off.

All the definitions were off.

And all the interpretations were off.

Blessed with the understanding of a new framework of neurodivergence that finally made sense, I finally see how those of us living our neurodivergence every day experience something very different from how other people describe what our experience looks like to them.

So whether you’re in the late-diagnosed camp (hi!), suspecting but not sure, or have no idea whether any of this has anything to do with you, here are just some of the things I wish I knew.

How clear ADHD & Autistic traits can go under the radar

I never looked like the stereotypical poster child for ADHD or Autism — the hyperactive blonde boy climbing trees or the withdrawn blonde boy stacking trains.

Maybe that’s why every neurodivergent trait and reaction I ever expressed as a child was dismissed as something else. This is so common you might already have your own list. Here’s mine:

My straight-to-the-point, direct speech style, and my often monotone way of delivery were often misunderstood as rude, even confrontational.

And I assume my being a woman didn’t help — I could never be “assertive”, only “bossy”.

Being a wriggly worm, constantly swinging in my chair during class, punching dot illustrations into my eraser with my pencil, finding split ends in my hair, and doodling at the margins all the time. All simply labelled as “having a poor attention span” and “daydreamer”.

Now I know I managed to focus in school not despite my fidgeting but because of it. To this day, stimming helps me focus and concentrate even on the things that I don’t find interesting by default. (Except now I crochet during meetings.)

My intense interest in various topics from Egyptology to planets, paired with a deep-seated need to correct those who had their facts wrong. Children. Adults. Teachers. Earning me the labels “obnoxious” and “precocious”.

Over the decades, I’ve learned the massive importance (and mental health benefit) of cherishing the time I can spend on the things that make me excited, and I will not be ashamed for any of it.

My nervous bathroom breaks before school on days I had gym class.

I dreaded the echoes of screaming children bouncing around the auditorium. The smell of sweat mixed with deodorant. And thinking back to the certain knowledge that a full-speed dodgeball will slam into me at some random moment still makes me shudder.

Back then, this was explained away as me “being an anxious little girl”. Today I recognise it as the sense of sensory overwhelm.

Noticing patterns in people’s behaviours — and then blurting them out. This often got me in trouble for being a “know-it-all”, especially when the person in question themselves had no idea of the thing I pointed out. No wonder I immersed myself in crime stories when I was 13 and promptly started writing detective novels of my own.

Even though I didn’t end up as a private sleuth as my youngling self imagined, there still is no substitute for the rush of connecting the dots, finding the meaning behind seemingly unrelated things, and then arranging them into logical systems.

So don’t worry, little one, I kept my promise and find clues for a living — they just lead to strategies and frameworks to help out people like us, instead of revealing which of the Pickwick triplets did it.

(Do let me know down in the comments how many of these you nodded along to!)

The mask I didn’t even know was there

All the things mistaken for something else are just one part of the picture.

The real answer to the question “why did no one notice” lies deeper.

In something hidden even from myself.

You see, so many people, by which I mean those not intimidated by my traits, would tell me how very organized, put-together, serious and goal-oriented I am.

And I did look the part — when I was doing well. When I slept enough, ate enough, when my hormones were in balance, when my mental health was okay. And for the longest time, that felt like a once-in-a-blue-moon event: mystical, unreproducible, controlled by the whims of some unseen force.

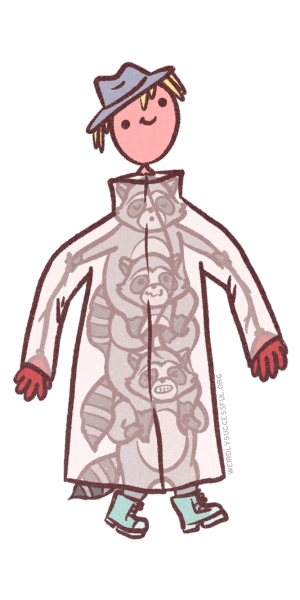

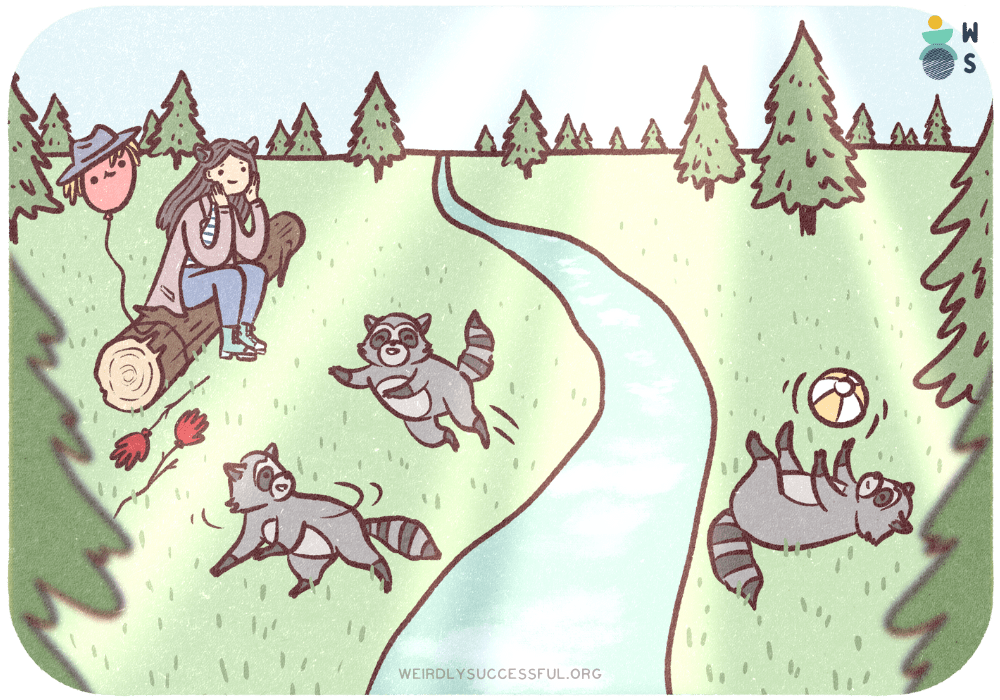

For me, the real reason I looked okay was because I was three raccoons in a trenchcoat pretending to be a human being — held together with duct tape, willpower and the overwhelming fear of being found out.

The trenchcoat hid as many neurodivergent traits that would fit under it.

This was my way of masking — that involuntary, unconscious behaviour to hide, suppress or minimize anything that would “give away” who I really am.

It wasn’t conscious. And it wasn’t meant to deceive. It was protection: to fit in, to function, to survive.

And many times, even when I wasn’t doing well didn’t give me away, because I wasn’t there. When the raccoon strategy broke down, the pressure was too much and I could no longer force myself to play the role of “Person Who Knows What They’re Doing And Are Not At All Overwhelmed By The Noise In This Place“.

When that happened, I simply didn’t go. I cancelled. I dropped out. Gave up. Quit.

To people who only saw me when I was doing okay, or when my mask was firmly on, it was unfathomable that I’d be anything other than an extroverted, happy-go-lucky, ‘a bit weird but overall okay’ person.

It made no sense.

I was always “so chatty” – except when I felt unheard and then retreated from the conversation, hiding in the corner without most people noticing. “You went quiet there”, some perceptive friend would say later. “I’m just tired”, I’d lie because even I didn’t understand what was truly going on.

I was always so eager to do things — except when I had to cancel last minute because I didn’t have the energy to brush my teeth and I could not go without, so I didn’t go at all.

Everything always came so easy to me — except they never witnessed the effort I put into things, nights spent trying to memorize, write, create the bloody thing, my brain spinning around in my skull in the stale gazpacho of thoughts that just couldn’t seem to go away, ever.

I always remembered everything — except I didn’t (and still don’t), and I had to keep meticulous records of even the tiniest things to keep up with things wanted from me and even with things I wanted to do. I’d lose my head if it wasn’t attached to my neck — or if I wasn’t so scared of falling apart that I “anxietied” my way into functioning.

Accepting who I am and how I am

For me, there wasn’t ever a moment of “there must be something wrong with me”. What I felt was exhaustion and the defeated acceptance of this is just how things are for me. I couldn’t relate to many things others my age were talking about — the activities they enjoyed that could be used for interrogation on me. The goals they could set and then achieve with methods that made no sense. “Just decide you want to do it, and then do it!” …what?

Things didn’t make sense and were kind of making sense at the same time.

I knew something was different, but how I worked had a system and logic that made sense to me, so it never occurred to me that I was in any way broken.

I am grateful to my parents for never, ever saying anything like that about how I was, and how they unconsciously modelled acceptance of their own internal workings for me. So partly because of them and the supportive friends I picked up along the way (all of them neurodivergent themselves, as it turned out), as I left the ‘fit in to survive’ world of school and went through my twenties, I gradually stopped trying to adjust my inner world to other people’s expectations.

Raccoons on the loose

Every year, on my birthday, I joke that the universe upped my daily dose of “DontGivaShitophen” once again. The biggest recent upgrade: once the concept of neurodivergence came into the picture, weird habits suddenly had names and inner workings were no longer isolated incidents but well-documented community experiences.

And that’s when after so many years, slowly but surely, I started allowing the raccoons to venture outside the trenchcoat.

First to go out the window was the panic of being found out. instead, I felt incredibly liberated to consciously seek out and create spaces for myself where pretending is not a necessity for survival.

Anxiety went next, as I found more and more evidence that I could be safe in these spaces.

And finally, I let go of that sheer will to keep the trenchcoat duct taped together.

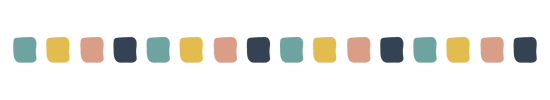

I cut the tape and let the raccoons out, wiggle their little feet as much as they wanted to, roll around in the grass while screeching at the frogs, wash invisible socks in puddles, or munch on carrots while curled up on the couch.

How I use masking as a tool

We still use the trenchcoat, the raccoons and I. It’s still necessary for situations where raccoons are prejudiced against and treated as less than. But knowing that I decide to put on the trenchcoat and I don’t have to wear it forever, it feels less like a hostage situation and more like fancy dress. We’re playing, we’re having fun by dressing up as Adult Talking To Helpline About Tax Forms and Woman Having Pleasant Small Talk While Buying Apricots. It’s still hard, but not as forced; not always.

And by now I’ve learned how and when to test the waters by letting one little raccoon ear poke out of the coat, to see if the other person is open and accepting enough. Often, this results in them showing a little raccoon wave from their coat in return, and suddenly, there’s a real, raw human connection that wasn’t there before.

After all, namaste means the three raccoons in my trenchcoat recognize the three raccoons in yours. Or something like that. I don’t remember correctly, I didn’t write that one down.

I’d love to hear your stories in the comments, please share. It’s a virtual raccoon playdate, y’all. 🙂

I accidentally built a glossary of neurodivergent terms

I accidentally built a glossary of neurodivergent terms

This is great. I’ve always been ‘three raccoons in a trenchcoat’ but until about ten years ago I found that I could simply identify as a ‘boffin’. These days, that’s not really a ‘thing’ and I was diagnosed level 1 ( = asperger’s) earlier this year at age 50. I’m still coming to terms with the world changing around me.

Hi Adam,

I love boffin! So fun to say, too. 🙂

Congrats on your late diagnosis! I found mine equally relief and grief and confusion inducing. Things finally make sense AND I have to relearn and unlearn a lot of things, many of them are internalized beliefs of who / what I should be. I’m happy you’re here, hope our site can aid you in this part of your journey. 🙂

It is puzzling. It’s like being told by your doctor “ah, Mr. W., the reason for all your problems is that you’re ugly!”. Why is society suddenly less tolerant of ugly people? Should I wear a bag over my mind?